Pilgrims kneeling before the shrine of our Lady of Lourdes, via Wikimedia Commons and the Wellcome Collection. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

It must have been clear, as John Broderick wrote his first novel, The Pilgrimage, that it would be banned by the Irish censorship board. (This was almost a badge of honor at the time for Irish writers. Brendan Behan’s Borstal Boy was banned in 1958, Edna O’Brien’s The Country Girls in 1960 and John McGahern’s The Dark in 1965, joining books by Balzac, Hemingway, H. G. Wells, and many others until the law was reformed in 1967.) His 1961 exploration of religiosity and sexuality is fearless and frank and sometimes comic. In the opening chapter, we hear the devout Glynn family—husband Michael, wife Julia, nephew Jim—conclude their plans for a pilgrimage to Lourdes. In the last paragraphs of the chapter, the visiting priest, chief promoter of the trip, “loosened the cord of his habit, and belched.” And then: “He belched again and then made the sign of the cross hazily in the air.” Soon afterward, Julia Glynn, in the guise of the faithless wife, goes to her bedroom “where her nephew was already waiting for her.”

It swiftly emerges that, despite their adherence to the Catholic faith, the four main characters in The Pilgrimage set about breaking the commandments—the ones that deal with sex and marriage—in both thought and deed and with some regularity. What Broderick is attempting is a French novel set in an Irish town; he wishes to put dangerous liaisons into the Irish midlands, to allow his Irish characters the freedom to pray to God for their eternal souls and then get into a state of mortal sin with agility and ease.

John Broderick was born in Athlone in the Irish midlands in 1924. He was an only child, expected to take over the family’s thriving bakery. He was brought up in a large house, and, while he worked intermittently as a book reviewer, he had a private income and did not have to bother too much about the literary market. In a posthumously published story, he described himself as “the first author to tap a hitherto neglected mine of material. Irish life up to this time had been treated as if it consisted of a passionately poetic peasantry, and a romantically rakish Anglo-Irish gentry. The solid, Jansenistic, purse-proud, insular, ruthless, hypocritical, conservative junta which has emerged as the ruling class since the [1916] Rebellion, has remained unchronicled for the simple reason that it had not produced a renegade of genius from within its own ranks.”

He was concerned, as a homosexual artist in a conservative society, to stir things up, to paint a portrait of an Ireland where conservatism and religiosity were merely veneers. He put much energy into giving even his most staid characters a rich, varied and adventurous sex life. “Everything happens in real life,” Julia says to her lover in The Pilgrimage. “It’s only in novels that it doesn’t.” Broderick sought to rectify exactly that.

In Seán Ó Faoláin’s short story “Lovers of the Lake,” published in the late fifties, Jenny, a married woman, is having an affair with Bobby, a surgeon. In the story, Jenny spends two days at Lough Derg, a famous site of pilgrimage in the west of Ireland, in the company of Bobby. The circumstances are similar enough to those in The Pilgrimage that it might be tempting to wonder if Broderick had read Ó Faoláin’s story, or was influenced by it. But the truth is likely to be more interesting. In these years, for many Irish people, a pilgrimage to Lourdes was as close as they would get to Continental Europe, and a trip to Lough Derg was a sort of holiday. Or, for a couple, an alibi. Toward the end of The Pilgrimage, a priest says: “I’ve known many happy marriages to begin in Lourdes … Indeed it’s a wise bachelor that goes on a pilgrimage.”

It was believed that Lourdes’s water had a special power, and it was customary to carry some back in plastic statues of the Virgin. In sermons, the faithful were admonished not to see the Lourdes pilgrimage as a spree. I have a memory of the priest in the pulpit in my town in the mid-sixties warning pilgrims not to stray into Spain for easy sunshine and cheap souvenirs. But they did. And some of them traveled also to Rome, as Michael Glynn hopes to do.

Glynn is a devout old man with many ailments, looked after faithfully by his manservant, Stephen, and more intermittently by his wife, Julia, who has no children, and his nephew, Jim. Jim, like the lover in Ó Faoláin’s story, is a doctor. This is no great coincidence. In Ireland of the fifties and early sixties, doctors, in the absence of an aristocracy or a millionaire class, were at the pinnacle of the social scale. This left them free and above reproach, at least in fiction, to pursue the bored wives of rich men. No one would think it strange for a doctor to be seen calling into a house that was not his own.

Likewise, Julia’s relative wealth allows her unusual autonomy. She has servants, travels back and forth to Dublin and sleeps in a separate bedroom from her husband. While other writers of Broderick’s generation, such as O’Brien and McGahern, wrote about hidden sexuality, no one had written about the secret erotic life of a most respectable woman in a small Irish town. Broderick does nothing to make us love the men in her life. Jim repeatedly refers to her as a “whore.” When Stephen begins an affair with Julia, his visits to her bedroom often lack tenderness. At best, he makes love to her in a “coldly passionate manner.”

For a time, Broderick allows the reader to feel that all the men in his book are at least bisexual. Even Jim’s attack on homosexuals to Julia is too oddly insistent: ” ‘Those god-damn queers!’ he burst out. ‘Sometimes I think the whole of this city is queer.’ He threw back his head and laughed. ‘Except me.’ He steadied himself and looked at her with narrowed eyes, his mouth curled in a leer. ‘Except us. We’re not queer, are we Julia? We’re just two old-fashioned bastards.’ ’

Michael is queer, as are some of the minor characters. Nobody believes, however, that Michael is anything other than a sick and saintly man, and his wife his long-suffering companion. In the small town of the novel, Julia had “developed a natural gift for dissimulation to an uncanny pitch of perfect. The city dweller who passes through a country town, and imagines it sleepy and apathetic is very far from the truth: it is as watchful as the jungle.”

Broderick continued to write fiction that cleared a space in the jungle so that its wildness could be more easily seen. He would go on to write eleven more novels, including An Apology for Roses (1973), which sold thirty thousand copies in its first week of publication. But there was a price to pay for any Irish writer in the early years of the Irish state.

The novelist Kate O’Brien, who also wrote about same-sex love and religion, and was as much an alcoholic as Broderick, spent most of her life outside Ireland, dying in Kent, in England, in 1974. Edna O’Brien moved to London early in her career and remained there. When John McGahern’s The Dark was banned in 1965, he lost his job as a teacher in Dublin and moved to England for a number of years before returning to live quietly in the Irish midlands. These three writers, like Broderick himself, were often viewed as outcasts in Ireland.

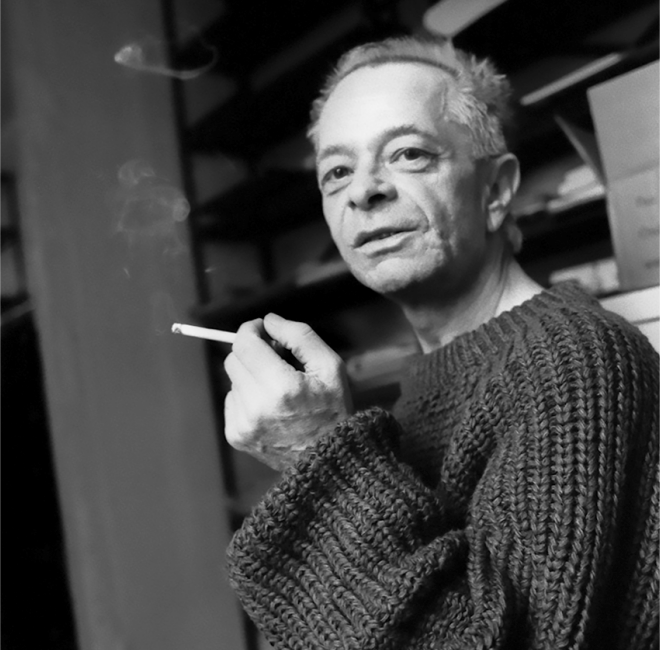

I saw John Broderick once. It must have been about 1980. He was in the corner of the bar of Buswells Hotel near the National Library in Dublin one afternoon. I caught his gaze for about thirty seconds. He was wearing a beautifully cut three-piece suit with elaborate stripes. He was alone and he looked desolate. Although there were many literary groups and cliques in Dublin, he was not part of any of them.

While he could review some books with great enthusiasm, he also wrote bitterly about other authors, indeed whole movements. For example: “Of all the various fads which have rippled across the literary scene over the past two hundred years symbolism was undoubtedly the silliest, and the most sterile.” And the axe of Athlone could be wielded on the neck of even the most famous, including W. B. Yeats: “The old poseur spent his life fooling the mob with mystical roses, most of them artificial.” Or: “Joyce will revert, if he has not already done so, to the universities.”

In 1981, John Broderick moved to Bath in England, where he died in 1989. In his lifetime, he never had the high literary reputation of writers such as John McGahern or Edna O’Brien, or indeed John Banville, whom Broderick had championed. At times, Broderick’s account of decadence in the Irish midlands seemed far-fetched. No one, it was believed, in a small town could be having that much sex. But life, or some of it, caught up with Broderick’s fiction. While the religious aspects of The Pilgrimage faded, and the priest, once an essential ingredient in an Irish novel, moved into the shadows, Julia Glynn’s hunger for life became almost everyday in Ireland and Stephen’s shedding of his own servility a metaphor for how the society changed. What Broderick had imagined slowly came into being.

Colm Tóibín’s most recent book is Long Island. He was interviewed by Belinda McKeon in issue no. 242 of The Paris Review.

Colm Tóibín’s most recent book is Long Island. He was interviewed by Belinda McKeon in issue no. 242 of The Paris Review.

5 months ago

121

5 months ago

121

English (US) ·

English (US) ·